Risky Solar Peaks - a Power Market Dystopia

A perfect spring weekend: the sun is shining from a bright blue sky, a pleasant breeze is blowing. While most people are enjoying this dream weather, one group of people is starting to sweat: power traders. As the sun rises higher in the sky, so does the amount of photovoltaic (PV) energy that is being fed into the grid, causing prices on the power market to fall. And they don't just drop to zero, they turn negative. This means: whoever sells, pays.

Negative prices on the European power markets are no longer a surprising exception, but a regularly recurring phenomenon. Or, to be more precise, a regularly recurring phenomenon that is becoming more acute every year in light of the rapid expansion of PV. However, solar feed-in alone is not responsible for the surplus situations with negative prices – it is a complex interplay of curtailment barriers on the renewable side and an inflexible conventional generation base that cannot respond adequately to the fluctuating supply of renewables.

But what do negative prices actually mean in practice? What happens on the power markets and in the electricity system when, in the end, no one is willing to buy electricity – even if they are offered three- or four-digit sums per MWh? Simply because this electricity cannot be consumed anywhere. Welcome to our little power market dystopia.

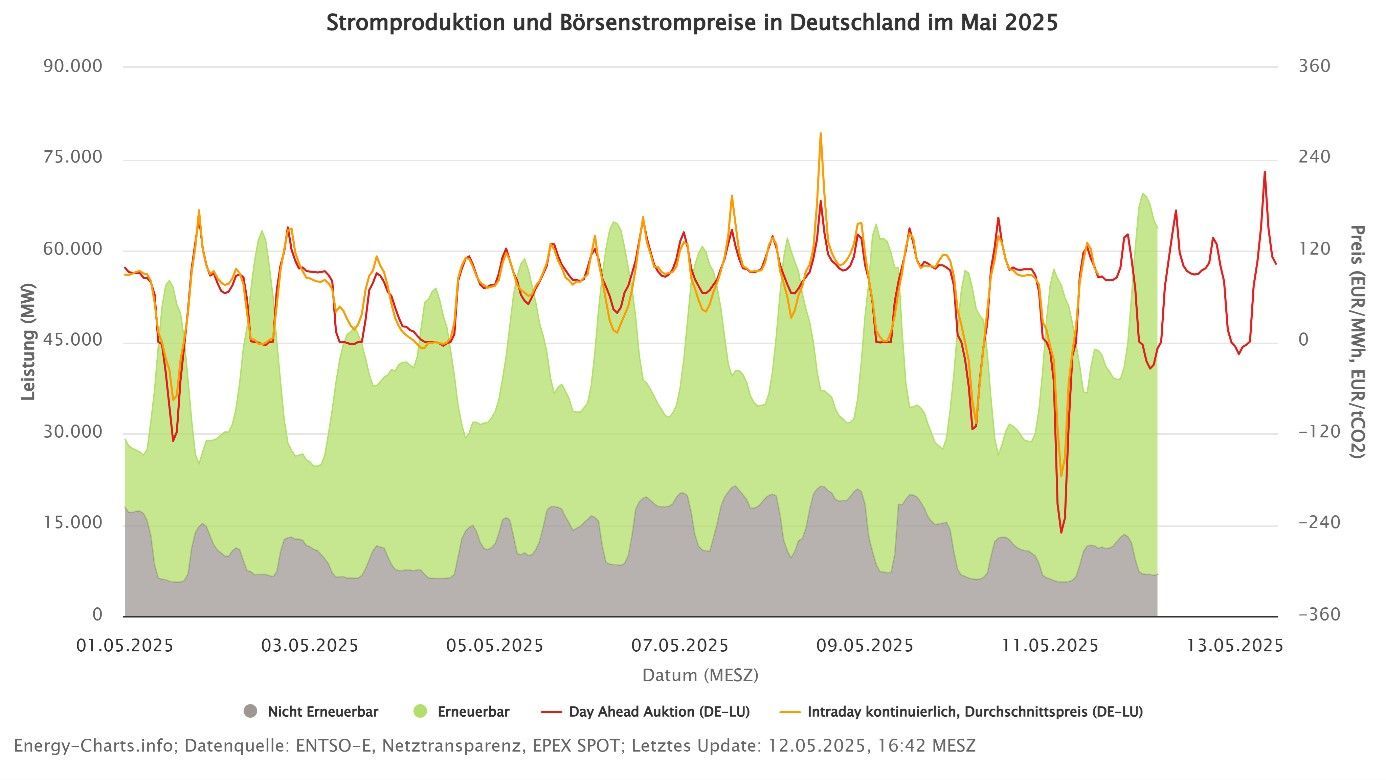

Negative Prices Are Rising Rapidly – Getting Closer To The Floor

While there were 301 negative hours on German power markets in 2023, there were already 475 hours with negative electricity prices in 2024. These figures are expected to be significantly exceeded again this year. In April and May, there were already numerous days on which prices slipped into negative territory. Take Saturday, April 6, for example: Not only in Germany, but across Europe, there was a reported oversupply of solar power. At the start of the merry month of May, the mood on the day-ahead market was also in the doldrums. The price fell to -129.99 €/MWh at midday on May 1. The downward slide continued over the weekend of May 10-11: On Sunday, prices were consistently negative across much of continental Europe between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. Between 1 p.m. and 2 p.m., the price plummeted to -€250.32/MWh in Germany and even to -€462/MWh in Belgium, not far from the day-ahead price floor of -€500/MWh.

Actually, we already reached this absolute low point from a day-ahead perspective once in 2023: On July 2, 2023, prices fell to -€500/MWh. According to ENTSO-E data, the feed-in was significantly higher than electricity consumption at 49.7 GWh during the hour from 2 p.m. to 3 p.m., compared to 46.1 GWh.

Pro Rata – When Supply and Demand Don't Match

What exactly happens when we reach the floor price of -€500/MWh in day-ahead trading, meaning that the market cannot be cleared? Let's take a closer look:

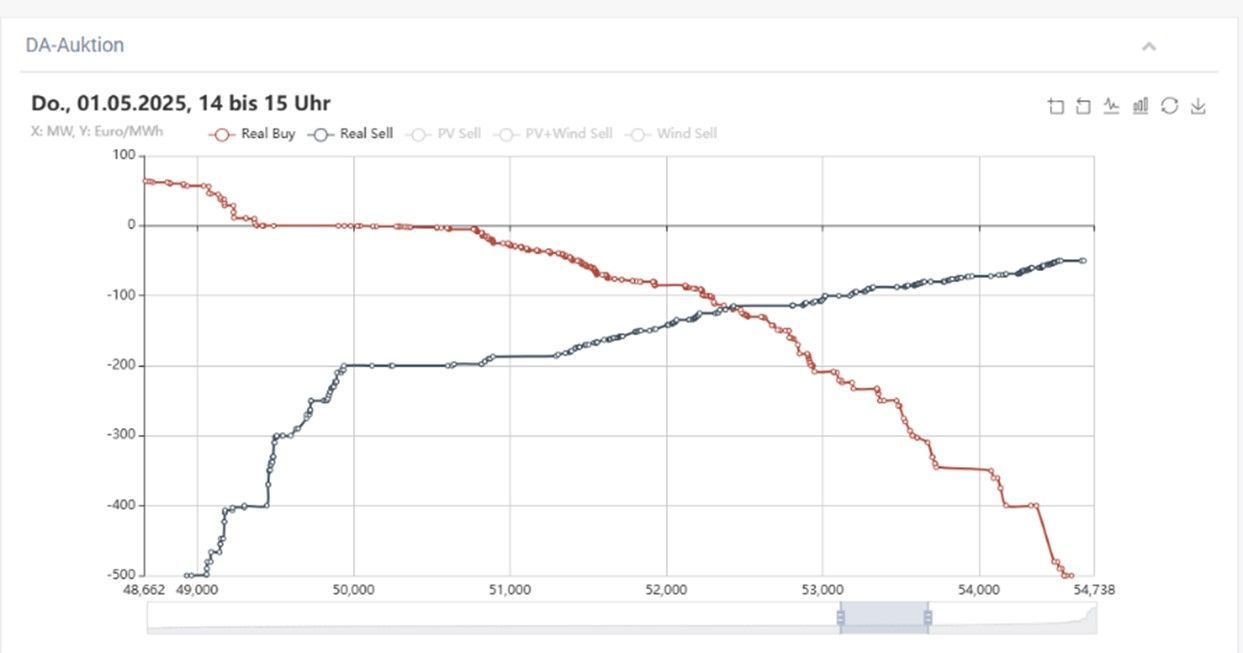

The chart shows price formation on the electricity market: At a certain price point, the supply curve (blue) meets the demand curve (red). In our example from May 1, 2025, the intersection point, i.e., the marginal price, is around -129 €/MWh. In concrete terms, this means that all electricity on offer found a buyer at this price.

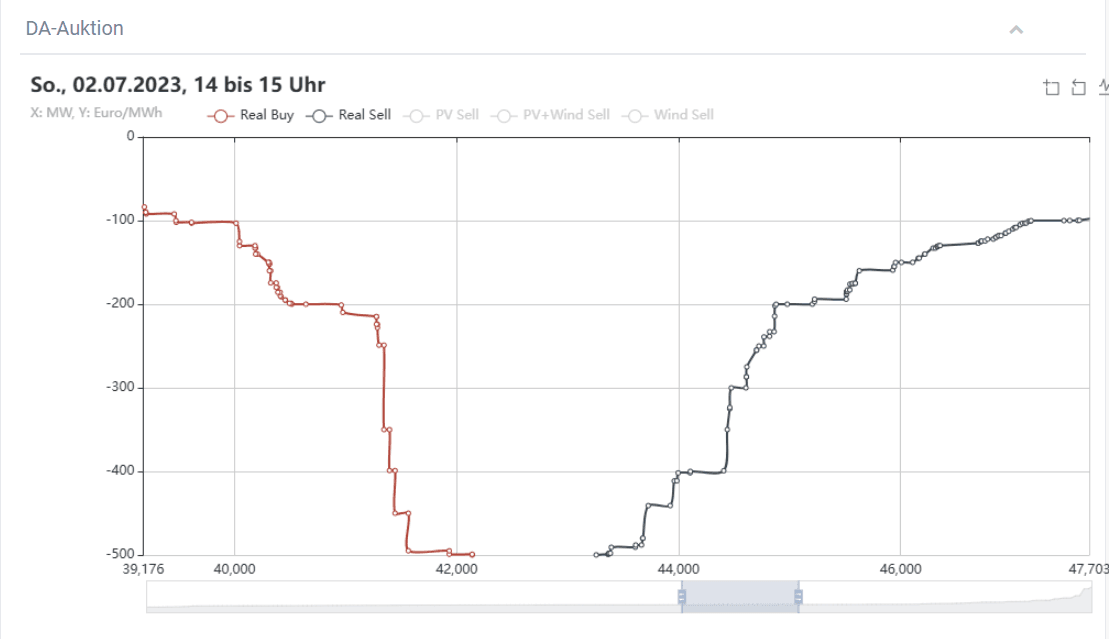

But what happens on the electricity exchange when supply and demand no longer align because the floor price of -€500 was reached, as was the case on July 2, 2023?

In this situation, pro rata allocation comes into effect. This means that demand is met in full, but only a partial allocation can take place on the supply side. Here is a simplified example to illustrate this: On July 2, 2023, between 2 and 3 p.m., demand was around 42.1 GW, but supply was 43.2 GW at a price of -€500/MWh. Consequently, the pro rata allocation was approximately 97.5%. A seller who wanted to sell 100 MWh could only sell 97.5 MWh and was left with an open position of 2.5 MWh after the day-ahead auction.

A small side note: The floor price of -€500/MWh can be lowered in further increments of €100/MWh if the price falls to a critical level of 70% of the floor price again within a month.

Negative prices in Day Ahead and Intraday + balancing energy = existence-threatening trading costs

However, the Day Ahead market is not the bottom limit. We leave the market, which is not balanced at closing time, and enter the intraday trading floor, where quantities are traded during the day. If the fundamental situation remains unchanged, the oversupply in intraday trading will continue. This means that power traders are still long, i.e., they want to sell electricity, causing prices to fall further. Incidentally, in intraday trading, the limit is not -500 €/MWh, but a dizzying -9,999 €/MWh. Anyone who is unable to sell their remaining quantities on this market ultimately has no choice but to run into imbalance: balancing energy is then requested for the open positions, which is billed to those responsible for the imbalances via balancing energy costs. The so-called reBAP usually goes down to -€15,000/MWh, but in theory, even more negative prices are possible if the scarcity component is used.

Back to our calculation example: If the example seller had to sell his remaining 2.5 MWh at an imbalance price of -€15,000/MWh, this would correspond to a loss of €36,250 compared to the day-ahead market. For the entire market (1.1 GW), the losses in this example add up to a total of around €16 million – for this one hour alone.

These enormous costs can lead to scenarios that threaten the existence of market participants. As a result, market players might try to adjust their supply curves in the day-ahead market – i.e., offer higher quantities than they actually need to sell – in order to reduce their share in the pro-rata allocation. This opens the door to complex game-theoretical considerations, which interested readers are welcome to explore further. However, this economic component is only one side of the coin. The consequences for the entire electricity system could be even more dramatic. This is because when such oversupply scenarios occur, the electricity grid reaches its limits. Let's take a look at the physical component.

Physical Feed-In – Steering, Rescheduling, and Curtailment

In general, power trader do not just place electricity on the exchange for accounting purposes. As operators of virtual power plants, they also strive to manage their pool in line with demand by reducing or increasing the physical supply according to price signals. This means, for example, that steerable plants such as bioenergy or CHP plants are shut down when prices are low and the electricity supply is correspondingly very high. If the price then falls below a certain point, steerable wind and/or solar plants in the pool are curtailed, which also helps to balance supply and demand in the power grid. Participation in the balancing energy market, where controllable power plant capacities are kept in reserve, also helps to stabilize the electricity system. If supply and demand cannot be balanced in the short-term markets, the grid operator calls on these capacities to prevent fluctuations in the electricity grid. In addition, grid operators take redispatch measures in advance: they change power plant deployment plans to avoid grid bottlenecks. There is therefore a well-designed, multi-level system with many safety nets to prevent critical situations from arising in the power grid. However, given the increasing solar peaks, we may reach a point where all this is no longer sufficient. One consequence could be that grid operators will have to disconnect individual areas from the grid in critical situations – in other words, small local blackouts will be triggered. This poses a considerable risk to the acceptance of the energy transition.

The Role of the Solar Industry

Let's return from these gloomy scenarios to the possible solutions. What can be done in this escalating situation? Many fundamental answers are already known and have been communicated many times: We need a better power grid infrastructure to transport surplus electricity to where it is needed. We need more flexibility through storage and flexible electricity consumers that can respond to peak situations. We need sector coupling, i.e., the intelligent integration of the electricity, heating, and mobility sectors.

But what we also need are better approaches to the operation and integration of solar power assets into the power grid: This is because a large proportion of solar power plants still feed electricity into the grid in an unregulated manner - even when prices are very low and there are not enough consumers.

The main problem arises from assets that are designed for self-consumption and are not controlled by market signals. These are essentially small rooftop systems with a fixed feed-in tariff. However, these currently account for the majority of new PV installations in Germany – and their operators have no incentive whatsoever to switch off their assets. On the contrary: the more they feed into the grid, the higher their revenues. This is because, under the fixed feed-in tariff, they always receive the same cent amount per kilowatt hour fed into the grid from the grid operator, regardless of the price on the power market. This means that when exchange prices are negative, the grid operator pays twice: once for the EEG remuneration to the plant operator and once for the feed-in at negative prices.

In German politics, the issue is already in motion. New, larger PV systems in direct marketing already receive no remuneration at negative electricity prices. A corresponding tightening of the 4-hour and 6-hour rules came into force at the beginning of the year with the Solar Peak Act. In addition, remote control is to be extended to smaller plant segments with the rollout of smart meters, and the direct marketing threshold is to be lowered. However, it must be taken into account that the value of the quantities marketed by plants optimized for self-consumption is extremely low due to feed-in at negative prices. To ensure that trading costs do not exceed revenues, a process of standardization and automation has been launched.

In addition to policymakers, the solar industry itself can also make a contribution with constructive solutions and the consistent implementation of remote control technology in existing assets. This will ensure that solar energy remains a success story and does not become a risk to the energy transition.

Note: Next Kraftwerke assumes no liability for the completeness, accuracy and timeliness of the information. This article is for information purposes only and does not replace individual legal advice.

More information and services